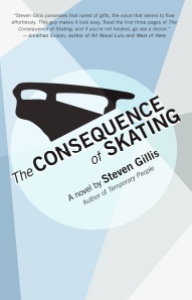

We’re pleased to present an interview with Steven Gillis about his recent novel The Consequence of Skating.

We’re pleased to present an interview with Steven Gillis about his recent novel The Consequence of Skating.

Black Lawrence Press: Early in the novel, the main character Mickey Greene intimates his belief that “at the heart of every conflict is just people dancing”. Is this something that you also believe to be true?

Steven Gillis: Without question. We are all basically an external extension of our own internal bullshit. We all just get our hackles up in a conflict and dance and strut and jump about with our egos aflame. Wars are nothing more than this, some “greater” and “larger” meaning propped up but when all is reduced back to its base root, its just people beating one another over the head with their own prejudices and misunderstandings. Even when we are fighting the good fight and our cause is noble and just, there is still a dance involved, by necessity, to get our point across. All human interaction is a dance. We’re animals. Watch animals as they interact, when courting, when fighting, its all a dance. People are no different.

BLP: In your last novel, Temporary People, you imagined an island nation experiencing one in a long series of revolutions. In The Consequence of Skating, all of the revolutions that have made the history books are synthesized, along with centuries of thought, by a computer program called Government Objectivity Design (G.O.D.). According to the program creator, this makes it possible to find logical solutions to all conflicts, even very serious conflicts that lead to war and revolution.

The hero of the novel would like to have faith in the program but cannot seem to muster it. In Temporary People, however, there is a legacy of people putting their faith in revolution. Do you think that, as it plays out in the worlds of your novels, revolution — or, at least, the possibility of revolution — is essential to maintaining faith in the future?

SG: Thats a good question. Jefferson said there is no possibility of a lasting democracy without a bloody revolution every thirty years. I don’t necessarily agree with this, but more so that revolutions are inevitable. No country is truly stable, and those that appear to be, like the United States, manage this by maintaining and manipulating its financial markets. If the markets crash far enough you’ll have a bloody revolution in the United States, too. We’re no different than the people in Zimbabwe or anywhere else. There needs to be a level of control – democratic, socialist, fascist, dictatorial – to keep a revolution at bay but in most poor nations the control is tenuous and the need to revolt is all an oppressed people have. But to your question, I think we are all as individuals in a constant state of revolt. If we are not revolting against something we are static. I don’t mean some angry revolt, I mean our ambitions are a form of revolt, we need to have personal revolutions, to be moving toward something. Absent that, we as individuals and then collectively as a community become complacent and apathetic and that is when dangers occur, when tyrants can take over a population, when our own individual dreams can disappear if we dont rally and revolt against our of insecurities and fears and find the strength to act. Action is life. Those who are afraid to follow their dreams I simply have no time for.

BLP: You have talked openly about the fact that your wife was diagnosed with breast cancer while you were writing this novel and that, through surgery, radiation, and chemo the writing of the book became a sort of anchor for you. How did this make the writing of The Consequence of Skating, different than the writing of your previous three novels?

SG: My life was totally different, everything was raw. I wrote from a need to have one constant – aside from the love of my wife and children whose lives were equally in a state of chaos. I wrote Skating all the while questioning the point of it all, the need to write yes to keep sane but at the end of the day could I say anything more in my work than realizing much of life is meaningless beyond serving the things we love? Maybe that’s enough to say. I still dont know if my state of mind was sufficient to even write Skating the way I wanted, though the reviews have been strong which is always nice. My perspective was so fucked during the process. A new level of focus was truly required. There were times I was writing while two feet away my wife was receiving 4 hours of chemo and how surreal was that?

BLP: The protagonist of the novel sets out to do a few things that are rather heroic. He’s in the research and development phase of staging Harold Pinter’s “Moonlight” and has created a fantasy-league cast list populated by some of the most talented actors that are alive today. At the same time he is also trying to overcome drug addiction. How do you think The Consequence of Skating fits in with other addiction literature titles that have come out in recent years?

SG: I don’t think of Skating at all as a piece of addiction literature. Mick isnt so much an addict as someone who got fucked up by a bout with drugs. Its not really who he is, or who the character is. The consequence yes, that is where the novel takes off from, after Mick’s sidetrack into drugs gets him in trouble. But I don’t think Skating is really a book about drugs. About addictions, yes. Without question. But drugs, no. You really have very little drug use or exploration of drug culture at all in the novel.

BLP: Harold Pinter’s work figures largely in The Consequence of Skating and is especially important to the main character. How has Pinter’s work influenced you as a writer?

SG: I love Pinter the man. I love his writing, his plays and how they deal with power and relationships, how people are constantly misunderstanding one another, how there is always a power play. I get off on Pinter’s exploration and explanation of language and its application in our interactions. Equally important to myself and the novel though is Pinter’s political positions, his fearlessness, his statements against war – dating back to 1947 all the way through Iraq. His Nobel Prize Speech is amazing. The courage of this man to say the things he did. This is what I love and the reason I chose to explore and employ Pinter in Skating.

BLP: Is your favorite Pinter play the same as Mickey Greene’s favorite Pinter play?

SG: I really love ‘Moonlight’ but it isnt my favorite Pinter play. ‘Moonlight’ served the text of Skating because of its subject and I wanted to use a more obscure and later work of Pinter. Personally, I am drawn to many of his early works, where the focus is on couples and the battle to sustain love – as ‘Moonlight’ does too, but in a broader and more fatal construct as the protagonist may well be dying and the focus is equally on his children. I had read dozens of Pinter’s plays before coming to ‘Moonlight’. If I have to list some favorites, they would be ‘The Homecoming’, ‘The Caretaker’, ‘The Lover’, ‘Betrayal’, they are all so great. Still, when it came time to choosing a work to employ in Skating, ‘Moonlight’ most perfectly fit the bill.